Thursday, September 24, 2009

I'm Starting to Immensely Distrust Philosophy!

So, this is what I gathered from Augustine. (And I truly read him because I felt like I needed to redeem myself (again) in class.)

The bit of his biography that was the most relevant to the class was such: " So long, therefore, as his philosophy agrees with his religious doctrines, St. Augustine is frankly neo-Platonist; as soon as a contradiction arises, he never hesitates to subordinate his philosophy to religion, reason to faith."

A red flag if ever I saw one.

With that in mind, I continued on to his writings.

The biggest thing that Augustine asserted and reasserted was the fact that Plato is a lover of God and that all philosophies Platonic were the closest to the church's doctrines and scriptures and therefore was the most trustworthy of all the philosophers, I guess is the word I'm looking for. In this sense, he didn't really ignore philosophers so much as pick and choose which ones were legitimate according to him and thus the church. I mean, I guess he paid attention to the philosophers, or rather philosopher, in this sense. He admits: " If, then, Plato defined the wise man as one who imitates, knows, loves this God, and who is rendered blessed through fellowship with Him in His own blessedness, why discuss with the other philosophers?" At least he admits his bias or preference.

He goes on to discuss the nature of the various heavenly beings-- " In every changeable thing, the form which makes it that which it is, whatever be its mode or nature, can only be through Him who truly is, because He is unchangeable." He synonymizes 'natural' with 'physical' in the Godly sense (a very Plantinga statement, haha) which manages to full circle back to Plato being Godly, etc. ("to philosophize is to love God").

The part that really struck me was his definition of the nature of philosophy:

" He is on his guard, however, with respect to those who philosophize according to the elements of this world, not according to God, by whom the world itself was made; for he is warned by the precept of the apostle, and faithfully hears what has been said, 'Beware that no one deceive you through philosophy and vain deceit, according to the elements of the world.'"

Now, I will grant that he is a God-fearing man, but that just seems to be unreasonable. I guess that's what I get for not being a theist, but it seems awfully silly.

Augustine is relevant in that I feel like he speaks a lot for the church, not necessarily that he is the church's mouthpiece or spokesman but that, simply, he represents what the church at the time probably thought. The real zinger is that Plato is probably the least (well maybe not the least) reliable source of astronomical rules/discoveries given his disposition regarding astronomy in general, which is disdainful. Hence my title. Plato plus Plantinga today really made me distrust the art of philosophy. Plato was this heralded man in the world of science (in general, philosophy, astronomy, you name it, people usually took his word for gospel--no pun intended) but in the realm of astronomy anyway, I just imagine Plato boredly describing these elabourate plans for the universe, waving his hand about in a holier-than-thou manner, not really giving a hang about it. And Augustine trusted it because Plato was similarly a God-fearing man and therefore he was the most reliable?

Meanwhile, back at the ranch, that fifth chapter of Sleepwalkers really helped wrap up the early theories of astronomy quite nicely. The succinct timeline/rundown of astronomers ending with the Ptolemaic [and perfected] model for the universe really ended that first bit well in that there is still a big chunk of the book left dedicated to completely destroying this "perfected" system. I mean, and for the time it was pretty perfected (well, I mean excluding the differences in brightness and size, but everybody at the time was pretty much trying to ignore that). It explained the speed ups, slow downs, retrograde motions, and it included the beloved circles. See my post before last for my Eureka moment.

How 'bout them apples?

RE: Alvin Plantinga (AKA modern day Plato)

(And I paraphrase...): "So, are we the end of evolution? God guided evolution to us since we are in his image, I mean, are we going to sprout wings or something? If not, why would God send his only son to die for us if we're only going to evolve to something greater?"

To which Plantinga replied something along the lines of, I don't know, "I don't have an opinion on that."

What good is a philosopher if you only want to give valid arguments that aren't necessarily sound? (For those non philosophers out there, a valid argument works within itself, that is Premise A and B do add up to the conclusion, but a valid argument requires true statements.) Isn't philosophy more than word play? It's about reality, existence, knowledge. You can't just make shit up, it doesn't work that way. (Excuse me, that was rude.)

Eureka! ...!?

In reading Koestler today, however, I got my Eureka moment. The top of page 81 wraps up a discussion on the continued myths of circles vs. ellipses, which was the discussion of the "failure of nerve" section as well. The very last sentence in the whole thing lays out failure of nerve right there!:

We shall see that, two thousand years later, Johannes Kepler, who cured astronomy of the circular obsession, still hesitated to adopt elliptical orbits, because, he wrote, if the answer were as simple as that, "then the problem would already have been solved by Archimedes and Apollonius."

I reread the sentence, underlined it, circled it, wrote next to it "failure of nerve" and then promptly got up to write this blog. It's too perfect! The reason why people hesitated to put out new ideas wasn't for fear of church persecution but for simple self doubt. The whole idea was that it would have been too easy to be right and by the same token that all the great philosophers and astronomers past hadn't put it out there first.

This is by no means the assigned blog for Friday, but I just thought I'd redeem myself a little bit. And by God, I hope I'm not wrong.

Monday, September 21, 2009

Oh, God, how did I not realize we had to blog today?

"The natural way of doing this is to start from the things which are more knowable and obvious to us and proceed towards those which are clearer and more knowable by nature; for the same things are not 'knowable relatively to us' and 'knowable' without qualification. So in the present inquiry we must follow this method and advance from what is more obscure by nature, but clearer to us, towards what is more clear and more knowable by nature."

Okay, right, great.

He goes on to expound on the nature of motion saying, "But all movement that is in place, all locomotion, as we term it, is either straight or circular or a combination of these two, which are the only simple movements," another granted thought from the time although, to be sure, it is without legitimate evidence.

The basic gist was that there is only one Earth and because the universe is without beginning, it is also without end and therefore indestructible.

Memo to self: What constitutes the heavens? And why are they necessarily spherical? Is 'heavens' synonymous with 'universe'? "That there is one heaven, then, only, and that it is ungenerated and eternal, and further that its movement is regular, has now been sufficiently explained."

Okay, so now that I've completely worn out my ctrl+c, ctrl+v keys, let's discuss a little Plato vs. Aristotle.

Plato, not being astronomically inclined and in fact being disdainful of it, has opinions simpler from that of Aristotle. Aristotle, I think, expounds on a lot of Plato's different thoughts but where Plato tries to use a lot of numbers, Aristotle uses only reasons and empirical observations. This makes perfect sense given the two philosophies on astronomy they have (well, duh).

Anyway, I've completely outdone myself stating the obvious today. Great job!

Wednesday, September 16, 2009

Revelations from the Phillistine

I thought I'd start the blog off with a little pop news humour. The God reference is sort of relevant to class!

Anyway, so, I guess I've always had a hard time with that very first diagram on the path of the sun. I think that was one of those diagrams I always briefly nodded at in grade school before quickly turning the page to hide my obvious incomprehension. Call it a "Eureka!" moment for me, having reread it just a couple days ago (I know, yikes, right?). Anyway, that was my first little glimmer of fascination. It had never really occurred to me why everyone complained about winter being sort of sunless, why the skies were usually gray. I just usually blamed it on being overcast (Yeah, but that often? Come on, Conklin). Well whatever my self prescribed answers were, I've got the real ones here. Boy howdy. Along the same line (oh, no, I'm about to make a really bad pun...), the concept of the ecliptic plus the earth's tilt never really made sense or at least that I never comprehended it until rereading it here.

I guess this whole little reading session really was just a big fun facts session for me. The concept behind the Zodiac and why each month long section got its own sign was interesting. I mean, I knew it had to do with stars, but what exactly or rather how was never clear to me. I just never thought about it.

I will say, though, that the concept of the sundial didn't really impress me though it seemed to be everyone else's source of excitement. Not that I didn't enjoy the concept, it was just sort of old news.

I will say, though, that the concept of the sundial didn't really impress me though it seemed to be everyone else's source of excitement. Not that I didn't enjoy the concept, it was just sort of old news.[at left, scene from Hercules: "Hey mack, you wanna buy a sun dial?"]

The technicalities of the solar/lunar eclipse were clarifying. I always sort of knew the basic gist, but the different positions of the earth along the ecliptic and the distance of the moon to the earth affecting the totality of an eclipse never really occurred to me.

So that's that. See you all in the vis lab!

Friday, September 11, 2009

Dense: hard to understand because of complexity of ideas

The density of an article or passage is directly proportionate to the amount of time I may spend dilly-dallying.

But, seriously, to be fair, being in my Intro to Philosophical Problems class and having to read Plato in this class (who is indeed a philosopher) makes me at least a little more patient than I normally would be whilst reading something so dense.

The first bit, The Allegory of the Cave wasn't so bad to read. I am rather fond of allegories and analogies (analogies more so because they're less subject to interpretation). The thing about allegories or analogies is that they’re never quite flawless because they are a comparison of sorts to the original situation, NOT the original situation. That aside, the Cave was pretty solid.

For sake of not summarizing, let me just point out some key points I saw. The comparison between the illusory shadows and the real deal being confusing to those prisoners who saw only illusions was a pretty interesting way of comparing the observations we make without evidence to the real scientific explanations. Plato uses a comparison of adjusting eyesight to adjusting perception of the world and the universe as well as comparing the “journey upwards to… the ascent of the soul into the intellectual world;” all of this he states in his final paragraph.

Now, maybe this is a cop out of interpretation, but he straight says his opinion is that, “in the world of knowledge the idea of good appears last of all, and is seen only with an effort; and, when seen, is also inferred to be the universal author of all things beautiful and right.” Why should I try to restate what he already says?

As for The Universe, the main points he makes as I see it are these:

1. God made order of disorder and made the world “a living creature truly endowed with soul and intelligence”

2. “In order then that the world might be solitary, like the perfect animal, the creator made not two worlds or an infinite number of them; but there is and ever will be one only-begotten and created heaven.” That is to say that there is only one world.

3. “That which is created is of necessity corporeal, and also visible and tangible.”

4. “The Creator compounded the world out of all the fire and all the water and all the air and all the earth, leaving no part of any of them nor any power of them outside.”

5. The world was created perfect and even and has a soul in the middle.

6. “The inner motion he divided in six places and made seven unequal circles having their intervals in ratios of two-and three, three of each, and bade the orbits proceed in a direction opposite to one another; and three [Sun, Mercury, Venus] he made to move with equal swiftness, and the remaining four [Moon, Saturn, Mars, Jupiter] to move with unequal swiftness to the three and to one another, but in due proportion.”

7. “The sun and moon and five other stars, which are called the planets, were created by him in order to distinguish and preserve the numbers of time.”

8. The sun was created to light the heavens and from that is night and day.

9. There are stars that behave in two manners: “the first, a movement on the same spot after the same manner, whereby they ever continue to think consistently the same thoughts about the same things; the second, a forward movement, in which they are controlled by the revolution of the same and the like

10. Everything is made of fire, air, water and earth (because they all make each other and come from each other)

Post, he goes to discuss the nature of humans. Let it be noted that our own very noggins are compared to the perfection of a sphere. I can’t tell if I think that’s funny or not.

Now let me say that the extent to which Plato described the process of #5 (the making of the Earth’s Soul) got pretty technical. It’s pretty impressive how technical you can get about something that doesn’t exist, I’d say. That’s probably the most interesting thing I read. It just never occurred to me that, while I may nod to their belief that the world is alive, I would never have thought to give it a soul.

#3 also struck me. It’s the whole concept of “If I can see it, it’s not there” sort of thing.

Maybe I missed something, but it seems to me that all of these points that I pulled are all things that we no longer regard as truth.

Wednesday, September 9, 2009

[Insert Lame Spherical Joke]

From what I can tell, the chapter isn't so much about failed nerves as much as various astronomers and scientists desperately trying to find explanations for piss poor hypotheses and/or statements by great philosophers taken for truth.

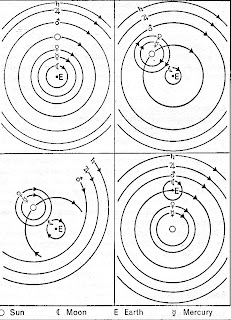

From what I can tell, the chapter isn't so much about failed nerves as much as various astronomers and scientists desperately trying to find explanations for piss poor hypotheses and/or statements by great philosophers taken for truth.The little section about Plato in chapter four compared with the diagrams on page 49 (see left) really made me, perhaps wrongly, giggle. It was just too perfect. Plato, this great know-diddly about astronomy making great claims about things needing to be perfect and in the end these astronomers were only trying to figure out logical explanations for the movements of these planets (bottom left of picture at right was quite ingenious, even if erroneous) while still maintaining this "natural perfection" of spheres and circles. The Plato vs. Aristotle section was interesting, too (starting page 53), including the section comparing Plato's Utopia to Orwell's 1984. Not having read 1984 (I know, right, what high school did I come from?), I guess I sort of miss much of the point, but I get the gist of it and it is indeed interesting.

As for the Greeks and their linear knowledge, I agree that knowledge progresses. I mean, we may agree that sometimes we may backtrack to old abandoned ideas and try to make them work again in new ways, but I wouldn't necessarily write that off as anti-progressive. I would not agree however, given the definition of linear (in a line or nearly straight line; or progressing from one stage to another in a single series of steps), that the pursuit of knowledge is linear. It may have the same sort of form as linear (an upward movement of more and more knowledge) but I see it more as a bunch of different lines instead of one single line-- and what is the line moving towards anyway? Is the upward movement signifying the volume of knowledge, per say? Imagine a tower of babel that keeps building upwards anyway despite the language/culture barrier and perhaps, expounding on this analogy, the tower is built in many a fashion and many a method, but continues to be build nonetheless.

Yeah, that just got a little out of hand.

Monday, September 7, 2009

Pythagorean Iceberg

That the Pythagorean Theorem is merely the tip of the Pythagorean iceberg is the perfect analogy. As we all read, Pythagoras was "an ancient radical," but huge nonetheless, achieving "semi-divine status." He developed these simple yet well thought out formulas and means of making these numbers work beautifully together. He even developed a means of tuning lutes and other stringed instruments, notably means that sounded poorly, "like a drunkard up and down the scale," not that it mattered, it was all about the numbers. Numbers were the root of everything.

When things like zeros and irrationals came into play, the whole system went kaput. The section "Zero" from Nothing Comes of Nothing mentions that the Greeks refused to acknowledge such numbers and kept the whole hole in their system under wraps. This is the parallel I saw between the truth of numbers and the truth of the universe (it should be noted that Pythagoras supported the idea of a geocentric solar system). Hippasus was thrown overboard for revealing the truth about irrational numbers, "for ruining a beautiful theory with harsh facts." I think that quote right there sums up the motivation. "Zero" ends its passage by saying "...it was not ignorance that led the Greeks to reject zero, nor was it the restrictive Greek number-shape system. It was philosophy. Zero conflicted with the fundamental philosophical beliefs of the West, for contained within zero are two ideas that were poisonous to Western doctrine."

More about this is sure to come in class.

Sunday, September 6, 2009

FSEM 131 Takes on Philly

The first thing I noticed was the hundreds (hundreds?) of different artifacts I guess I could say that were used to help navigate the seas (the discrepancy in country sized between the various maps were super cool). As Prof. Bary himself said, "I don't even know how to use half of these things." Imagine how I felt, haha.

The most striking to me however was, obviously, Galileo's telescope, the reason we traveled 10 hours (I say that very lovingly as that was some mad FSEM bonding). It just struck me as ingenious (again, thank you Captain Obvious) that Galileo could take a lead pipe with two plates of glass and completely verify the rewriting of the universe. It looked so simple, almost impossibly so and Galileo managed to observe the most fantastic of things.

What really struck me was that, however simple and ingenious the design, Galileo managed to perfect it in many a shorter time than anybody else possibly could (if I read right, right?). I don't really know where I was going with that other than that I thought it was interesting.

I love museums!

Thursday, September 3, 2009

Click on this for your life's purpose!

"He turned back to where Tiamat lay bound, he straddled the legs and smashed her skull ( for the mace was merciless), he severed the arteries and the blood streamed down the north wind to the unknown ends of the world.

When the gods saw all this they laughed out loud, and they sent him presents. They sent him their thankful tributes.

The lord rested; he gazed at the huge body, pondering how to use it, what to create from the dead carcass. He split it apart like a cockle-shell; with the upper half he constructed the arc of sky, he pulled down the bar and set a watch on the waters, so they should never escape.

He crossed the sky to survey the infinite distance; he station himself above apsu, that apsu built by Nudimmud over the old abyss which now he surveyed, measuring out and marking in.

He stretched the immensity of the firmament, he made Esharra, the Great Palace, to be its earthly image, and Anu and Enlil and Ea had each their right stations."

...What a maniac! Of course, after all this blood shed, he went on to take credit for the stars, the moon, the sun, the calendar, etc., and of course he could not be finished without making servants for the gods:

"'Blood to blood

I join,

blood to bone

I form

an original thing,

its name is MAN,

aboriginal man

is mine in making.

'All his occupations

are faithful service,

the gods that fell

have rest,

I will subtly alter

their operations,

divided companies

equally blest.'"

And so on and so forth.

As we all know, the contemporary Judeo-Christian tale of creation is a lot less fantastic and simpler. Everything was created in peace and harmony and in God's image as a sort of whimsical (perhaps whimsical is not the right adjective but that's what comes to my mind) thing that God wanted to do.

The only similarity I see involves the role of man vs. God(s) in which we were put on Earth as tools of God. The Babylonian myth describes us as servants, flat out, and while the Christian version (God forbid I say 'myth') doesn't exactly say we are God's servants in Genesis1, many Christians believe we are put on this Earth to do God's will and in that way so we are servants.

How fascinating! That was fun.

Tuesday, September 1, 2009

Galileo=True Old School Baller

I cannot say that I have personally observed any of these things that he notes, neither our moon nor Jupiter and its moons. I once looked through a telescope long ago at a wedding reception but not since and regret to say that I have never even taken an astronomy course. I'm not sure how far back that puts me in terms of everyone else's experience, but I'll do my best to keep up, I guess. As for my perspective, I, for the most part, take Galileo's observations as truths (keeping in mind that I as well read the footnotes that corrected his few errors). Observing for myself what he saw would only serve as reinforcement or verification.

Now, poetry is very much my Achilles heel and probably my least favorite form of writing, so I will try to do my best with our pal Lucretius. This poem was long and drawn out and at times didn't seem to relate at all to Galileo or the church or even astronomy, however I will admit that my ineptitude with poetry perhaps might contribute to this deduction. I will note what it appears everyone else has noted in their blogs (as it seems the most relevant, although I swear I saw it in the text as well) the lines about the "Bodiless and Invisible," as it seems most relevant to our class. I'm an aficionado of making sound arguments based on comparisons and analogies and that he relates the planets and what we cannot see to tiny particles, organs and microscopic objects too small for the eyes. In essence, he writes that it's senseless to talk down hypotheses regarding the existence of objects (planets) just because you can't see them. What he says about human nature relates to the idea that the same piece of information can be taken in different ways and some people may just flat out refuse to see it.

At this point, I feel like a total shmuck because the common cold is at its peak with me right now and the various liquids pouring from my face and eyes restrict me from doing anything involving having to read or even have my eyes open. I hope I do better next time... Jeepers.